Published Promise 2019

The Sisters of Providence founded St. Paul’s Hospital to provide compassionate care to anyone who needed it. Before long, nuns from other orders arrived in Vancouver with the same commitment to provide care and comfort to the citizens of the growing city. Today, as we prepare to move to the new St. Paul’s, those same values are threaded into every bed and across every unit.

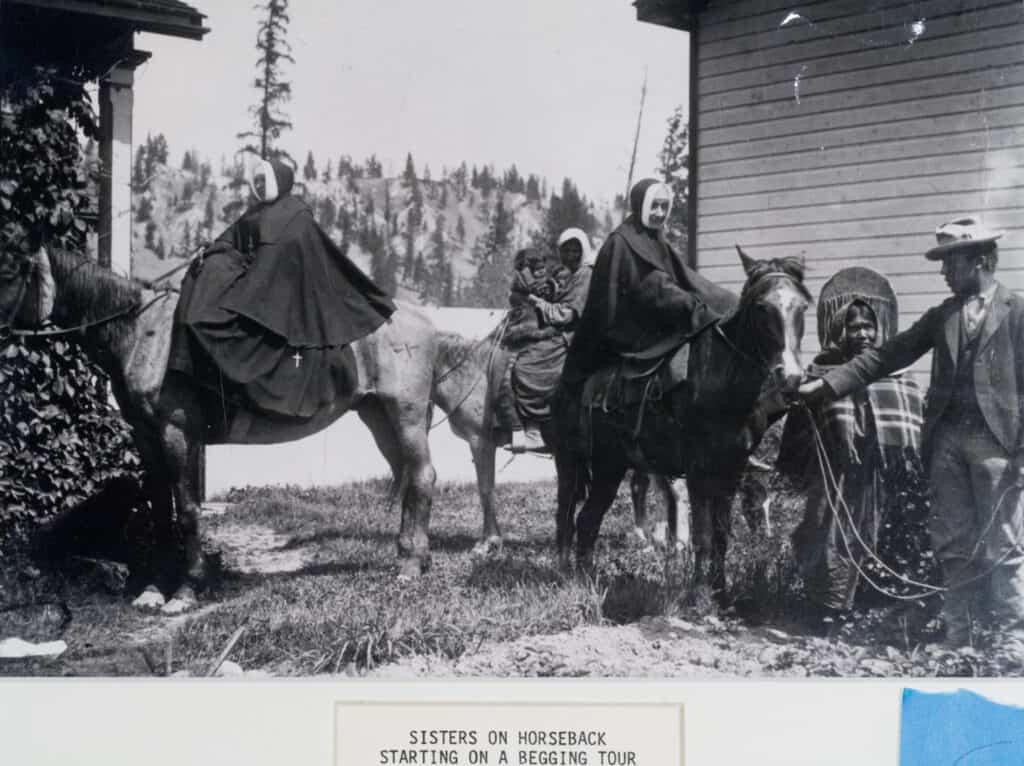

The sisterhood of travelling nuns

In the 1920s, widespread racism prevented Vancouver’s Chinese residents from getting the health care they needed. Responding to an urgent appeal for help, four nuns from the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception arrived from Quebec. They opened a clinic and four-bed infirmary in a little house on Keefer Street, in Vancouver’s Chinatown, and immediately began to treat the neighbourhood’s sick and impoverished residents. As the community grew, so did the need for more space to provide care. The Sisters bought an old sheep farm on Prince Edward Street and set about raising the money to build what would become Mount Saint Joseph Hospital (MSJ). The Grey Sisters arrived from Pembroke, Ontario, in 1931 and began caring for elderly men on Vancouver’s “skid row.” They went on to build PHC’s Youville Residence.

That same decade, the Sisters of Charity opened St. Vincent’s Hospital on the site now earmarked for one of two new dementia villages. The Missionary Sisters came from Kingston in 1947 and purchased a plot of land with a five-bedroom house which they quickly converted into a nursing home for elderly women. Today, it’s the location of Holy Family Hospital – one of BC’s largest rehabilitation centres as well as an extended care residence.

Grace in times of crisis

In the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, St. Paul’s was a beacon of hope to people devastated by the Great Depression. Thousands of Vancouverites lost their jobs; many were poor and starving. It became widely known that no one would be refused a meal at St. Paul’s. In the darkest days of the Depression, people would line up at the hospital’s side entrance where the Sisters would feed as many as 700 a day.

The 1980s brought more devastation when the HIV/AIDS crisis hit. In the face of province-wide panic, St. Paul’s did not waver. In 1982, when many hospitals were barring their doors, St. Paul’s became the only hospital in BC to knowingly accept and care for patients with AIDS.

Back then, very little was known about the disease or how to treat it. Homophobia and fear of contagion were rampant, but St. Paul’s continued to accept and treat everyone needing care. As the crisis deepened, this became increasingly poignant. St. Paul’s location at the gateway to Vancouver’s gay-friendly West End meant many of those early patients were staff members who lived in the neighbourhood.

Those tragic times brought another compassionate innovation to St. Paul’s: a palliative care unit (PCU). In an act of pure compassion, the unit integrated patients who had AIDS with those dying from other causes. It was the first in Canada to do so and marked a significant step in de-stigmatizing the disease. In the beginning, almost half the PCU patients had AIDS. “It was so important to the spirit of the nuns for St. Paul’s to respond to that crisis,” says Sarah Cobb, a clinical nurse leader with the program. “As treatments became available for HIV/AIDS, the ward shifted to care for people with other end-stage diseases.” Today, the Palliative Care Unit is an acute care centre transforming people’s understanding of end-of-life care across all PHC sites. “The specialty has evolved tremendously. It’s much more evidence-based. We’re seeing that it vastly improves the quality of life for patients and their families, and in some cases their actual prognosis,” says Cobb. “It’s about providing a highly-expert, evidence-based, and meaningful experience while recognizing people as human beings with different needs.”

Now Cobb is leading a pilot project to integrate palliative care practices across every unit, helping address the gap between the 90 percent of Canadians who need palliative care near the end of their lives and the 30 percent who will actually receive it. It’s just one more demonstration of how PHC is always reaching out to those who are underserved.

The next era of caring

“The elderly have always been a population of emphasis for St. Paul’s,” says Dr. Janet Kow, senior medical director of acute care and physician program director of elder care, which operates from St. Paul’s and MSJ.

“If frail seniors can’t speak for themselves, or don’t have resources, it’s our job to make sure they’re heard and looked after.”

Kow and her team are also developing the vision for the planned Centre for Healthy Aging at the new St. Paul’s. The Centre will be more than a state-of-the-art, integrated medical service hub for older adults; it will be an axis of research on how we can all age better. “We’re asking: How do we intervene early?” says Kow. “It’s a continuum from making sure that people don’t get sick, to keeping those who are starting to have some medical issues independent and maintaining their quality of life.”

Meanwhile, quality of life is the heart of a revolution underway at all of PHC’s residences. Megamorphosis, which began in 2017, is an intensive, site-by-site transformation in which staff, seniors, and family come together to overhaul established routines and find new ones that address individuality, emotional connection, and a feeling of home. Now a $3 million donation by the Jurazs family has allowed the team to refurbish the Holy Family residence. This project will become the blueprint for the Providence Residential and Community Care Services Society’s planned dementia villages on Heather Street at the former St. Vincent’s Hospital site and in Comox.

“Holy Family is a leap forward,” says Jo-Ann Tait, corporate director, seniors care and palliative services.

“All of this transformation is shifting our culture toward a vision of building places where you and I would want to live if we required care.”

The new Holy Family model is based on 12-person households where residents dine together, get outside, and take on meaningful tasks within the home. Innovative and creative senior-led design changes have been implemented, and the care model has changed to support seniors’ care more nimbly.”

“Seniors are not a homogeneous population,” says Tait. “Our approach has been grounded in understanding who people are, not just their complexities – what their hopes and dreams are at this point in their life’s journey. Our job is to try and help them reach their dreams. What we have also learned is that for some, this is the first time in decades that they’ve found home.”

To Tait, this human-centred approach to seniors’ care is just another way compassion is expressed at PHC. “When you look beyond the paint and the vibrancy, what we really value is emotional connection. And that happens between people, regardless of age, disease, background, or prejudices,” she says. “It’s how we connect with other human beings: that we see them, and hear them, and value them.”

Help support the next 125 years of compassionate care at St. Paul’s. Donate now.