Published Promise 2024

Christine was an energetic, young kindergarten teacher when she unexpectedly began to feel dizzy and short of breath during everyday tasks such as picking up toys and moving around the classroom.

At first, Christine’s doctor attributed her experience to stress, but as symptoms worsened – and with a family history of cardiovascular disease – she knew stress wasn’t the culprit. Eventually, at age 36, Christine was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heart rhythm that prevents the heart from pumping blood efficiently.

Christine received a pacemaker that improved her energy, quality of life, and ability to work – but unfortunately, those benefits didn’t last long. Pain, pressure, and breathlessness plagued her daily life.

“It felt like I was walking into a wall all the time,” she remembers.

Despite her health struggles, Christine and her husband were eager to start a family. Even with her symptoms, doctors assured them that Christine’s condition was well managed and she’d be able to have children.

They were gloriously happy when Christine became pregnant. But four months into her pregnancy, Christine received some devastating news: her heart was failing.

“I was quite shocked because I wasn’t expecting to hear that, and I didn’t really know what the words ‘heart failure’ meant,” she says. “The first thing I thought was, ‘What’s going to happen to my baby?’”

Despite her health struggles, Christine was referred to the Virani Provincial Adult Congenital Heart (VPACH) Program at St. Paul’s Hospital, where staff could monitor her pregnancy. She learned that while heart failure is serious, it doesn’t mean her heart would immediately stop beating – and that many people with the condition live healthy, full lives.

“It really helped to lift that seriousness of the diagnosis,” she says. “The VPACH clinic explained to me that the care on the maternity ward would be in conjunction with my heart care, and they’d be able to monitor me throughout my pregnancy and delivery. It gave me great peace of mind to know that they would have my back.”

Thankfully, with lots of support, Christine made it through her full pregnancy and safely delivered a baby girl, Melanie.

Over the next several years, Christine’s heart function deteriorated to the point where she needed a heart transplant. Miraculously, after only four months on the transplant list, she received a new heart in July 2019.

Transplantation is a team sport

When many of us hear the words ‘organ transplant’, we immediately think of the donor and the recipient. Undoubtedly, the people who generously decide to donate organs and those who receive them are a central part of the heart transplant process.

Yet there is also a vast network of health professionals working in concert like a finely tuned orchestra, including doctors, nurses, social workers, cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, radiologists, dietitians, and more. They guide patients through the process, from preparation to recovery, and provide care that’s grounded in compassion.

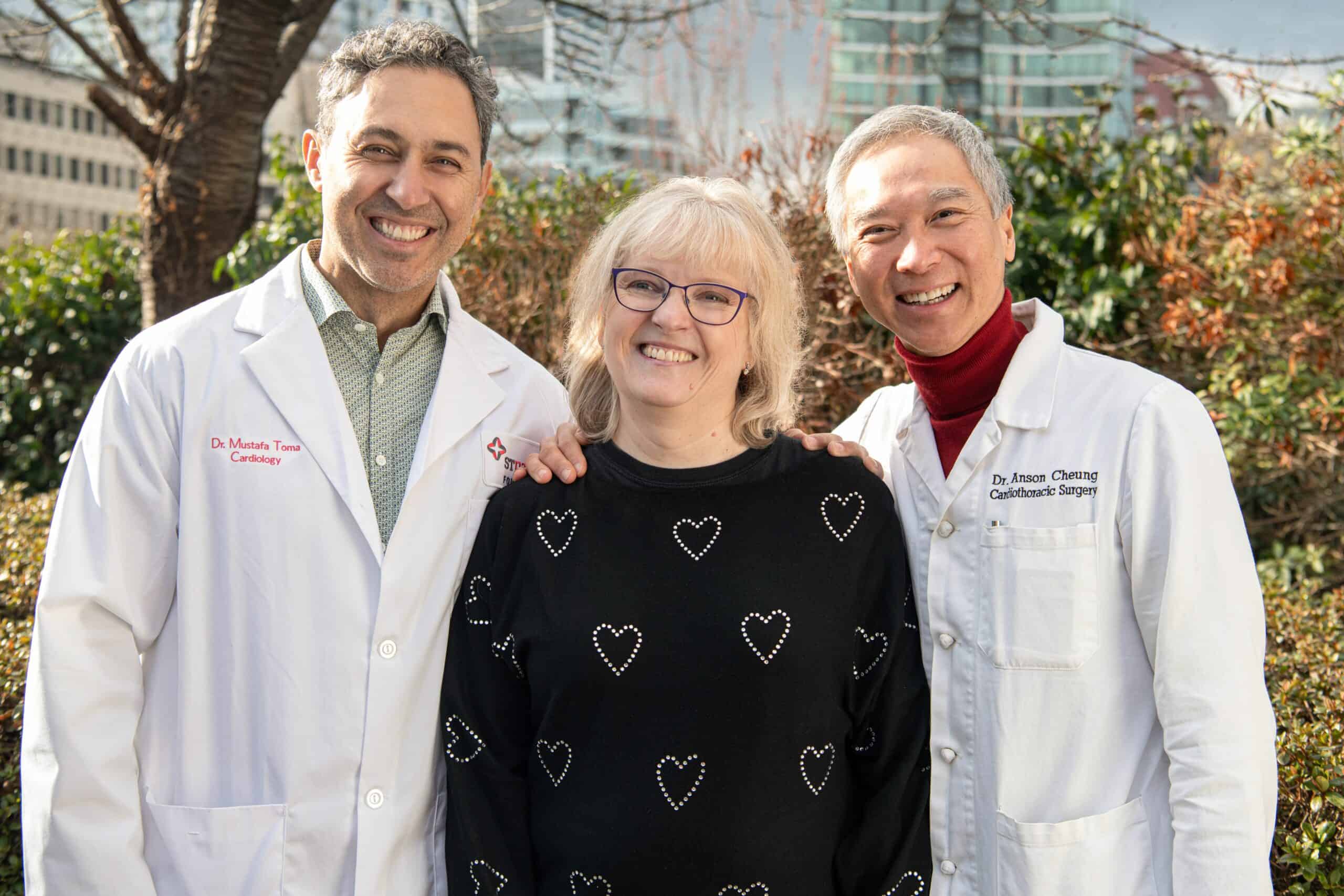

“Heart surgery is always a team sport,” says Dr. Anson Cheung, Christine’s heart transplant surgeon. “For transplants in particular, there’s an even bigger network of people that are required to be successful. In our hospital, everything starts with the patient at the centre, and then we rally and work together to surround the patient with the care they need.”

“My daughter was only seven when I had my transplant. I was just so scared about having to leave her. My new heart has just been a gift – the gift of time with my daughter, husband, and extended family.”

Christine Boutin

St. Paul’s Hospital is home to BC’s only adult heart transplant program. Since 1988, Providence Health Care (PHC) has performed 602 heart transplants on patients like Christine.

Dr. Mustafa Toma, a cardiologist who helped coordinate Christine’s pre- and post-transplant care, says there are countless caring individuals who collaborated to make a daunting and stressful situation less overwhelming for her.

“There are a whole lot of people working behind the scenes,” he says. “It’s essentially the entire team in our provincial Heart Centre that’s involved with transplant patients. Without a multi-disciplinary team, we really could not do this.”

Christine struggled with a few setbacks during recovery, but the rehabilitation team at St. Paul’s was with her every step of the way. Today she’s doing great, and takes immense pleasure in simple moments with her daughter Melanie, like swimming or racing to the mailbox.

“At St. Paul’s Hospital, I have faced some of the most difficult times in my life,” she says. “In other hospital settings, I haven’t received care that has been as consistently kind, caring, and thoughtful. Without exception, staff put me first and really listened.”

The new St. Paul’s Hospital and more broadly, the Jim Pattison Medical Campus, will enable us to further the delivery of PHC’s people-first model of care and explore new research discoveries that will improve patient lives.

Christine is also relieved to learn her condition was likely due to a genetic mutation, and happy to know that testing family members was a possibility. As she celebrates her five-year ‘heart-iversary’, Christine reflects on how far she’s come. She’s able to live fully with the people she loves, a prospect that was once unimaginable.

“My daughter was only seven when I had my transplant. I was just so scared about having to leave her,” she says. “My new heart has just been a gift – the gift of time with my daughter, husband, and extended family.”

Your gift will help us offer collaborative, transformative care at the new St. Paul’s Hospital and medical campus.